Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Keynote Description

|

Bill Pechet- Little Spirits Garden

This project was completed in collaboration with Daly Landscape Architecture. Located in Saanich, BC, Canada, the memorial garden is designed to honour the loss of infants, both pre- and post-term. It is the first of its kind in North America. A variety of commemorative elements provide for a range of needs. Little concrete houses, wind notes of wood veneer, tiny copper bells, and polished basalt spirit stones, all contribute to a peaceful and meditative environment for those who have lost their little ones. A ceremony pavilion constructed of corten steel echoes the colours and shapes of arbutus bark found on the site. The polished concrete and bronze altar is inspired by the shape of a heart. The rounded edges are designed to offer a comforting, maternal anchor during funeral ceremonies. This tiny village will eventually memorialize over 3,000 children. |

Speaker talk description

Dr. Candace Couse

Images in the media and medicine reflect and reinforce particular power structures. They direct how we understand and act upon sickness, fragility and death. Using the image through case studies in both domains, I address how morality is applied to illness and dying when we picture health in a framework that fuses moral goodness with ideal form. Culture and medical history have been infiltrated by ideal bodies and hero-figures. From medicine’s ideal body-object to popular depictions of breast cancer survivors as heroes who have conquered a villain, the antihero, death, is so often positioned as a chaotic lawbreaker violating the order and symmetry of the body. Sickness and dying seem to be proscribed a moral order and "good" manner of experience. We build shadowy rooms equipped with all the accoutrements of idealized victimhood, always waiting, always ready for the victim to arrive and take up residence. The victim is asked to mould their body to contour perfectly with the wound space in which they are placed. There is a mental and physical cost here: Gayle Sulik has written that this cult of goodness is so potent that the visible identification of moral superiority overrides practical efforts for alleviating the suffering of the disease politically, medically, scientifically and socially (133-146). As a counter to this imposed and ordered idealism of sickness, fragility and death, I am interested in the conceptual disorganization that the art experience provides. Far from finding a deficiency in the critical potential of conceptual disorganization, I look to the promise of this turmoil. What possibilities does a process that nurtures conceptual instability—the refusal to permanently reach a decisive conclusion—hold? How can this disorganization fit into the kinds of critical thought that dominate our ways of knowing, and what, if anything, does this mean for the subject matter represented?

I believe it is especially important to challenge medical clinicians and researchers to examine everyday viewing practices, because while they may have exceptionally specialized knowledge about the output from an MRI, they are no more immune to the power and symbolism contained in its aura than their patients. Indeed, perhaps it could be said that medical clinicians and researchers are even more interpellated,* for we are all entrenched in the myths of our professions. The art experience entails particular strategies for orientation with images and experiences (both biographical and immediate in nature) that I use as a rallying cry and multi-layered justification for the integration of art and arts-based methodologies into clinics, research and medical education, offering one theoretical foundation for the many empirical and qualitative studies that have shown that art-based methodologies can improve clinical observational skills, forge community, sociality and empathy between clinicians and patients, and more.

I believe it is especially important to challenge medical clinicians and researchers to examine everyday viewing practices, because while they may have exceptionally specialized knowledge about the output from an MRI, they are no more immune to the power and symbolism contained in its aura than their patients. Indeed, perhaps it could be said that medical clinicians and researchers are even more interpellated,* for we are all entrenched in the myths of our professions. The art experience entails particular strategies for orientation with images and experiences (both biographical and immediate in nature) that I use as a rallying cry and multi-layered justification for the integration of art and arts-based methodologies into clinics, research and medical education, offering one theoretical foundation for the many empirical and qualitative studies that have shown that art-based methodologies can improve clinical observational skills, forge community, sociality and empathy between clinicians and patients, and more.

Dr. Sonya Jakubec & Jennell Rempel

We all feel it – whether looking outside, in a field, at a beach, or on a mountain – nature gives us perspective about life and death. There is growing evidence of how natural environments impact our physical, mental and spiritual well-being. Little is known, however, about the place of parks and nature at the end of life, or the impact of parks and nature on quality of life during end of life…until now!

Supported by Mount Royal University (MRU), Alberta Parks, Alberta Health Services and the UofA’s/Augustana Campus’ Centre for Sustainable Rural Communities, this project undertook to explore the place of parks and nature in palliative care for people in rural communities. Building on 2 previous projects exploring parks inclusion for adults with disabilities and people in palliative care and their caregivers, the action research cycle included planning and visiting park sites for 1-3 hour visits for patients and families, sitting in green spaces, moving (assisted or unassisted, with a walker, or wheelchair) to a view spot of their choosing. Included in the project were 5 palliative patients and their family caregivers (including 4 spouses and 1 daughter), along with 2 rural home palliative care nurses and 1 rural hospice chaplain. Participant observations and opinions of the experience were explored. Together we discovered that experiencing “Peace in the Parks” was an opportunity for personal exploration, social discovery and park/institutional awareness.

Despite the challenges to get to parks and natural places, it was always “worth it” (and perhaps even more valuable for caregivers and family!). Everyone can make the connection with nature. Ultimately there is value in even parking or sitting in areas with views of nature or short 100 metre ‘walks’ or strolls with a stretcher or adaptive equipment. Access does takes planning, information and communication. Fundamentally, we discovered that supporting access to parks and nature for those in palliative care and their caregivers is not a call for a new program per se, but rather an invitation to the pilgrimage and sanctuary of natural places. It doesn’t always come easily or naturally but pilgrimages can be supported by a mindset influenced by training, information, and coordination. Further collaborative work is underway now to extend and expand the discoveries made thus far – the pilgrimage continues!

We most wanted to let the narrative from this project speak in the voices of our gracious park volunteers, the palliative patients, family, and professional caregivers – alongside the sounds and sites of Alberta Parks and other natural settings. The overarching narrative discovered, and the title of the short documentary film we will screen (approx. 10 min) and discuss is “Peace in the Parks”. The film can be viewed at: https://youtu.be/dkLSrzhwNzk

Rest in Peace [in the Parks] to the wonderful Bev, Ron, Liam, Garry and Maxine (with thanks to their family and caregivers).

Supported by Mount Royal University (MRU), Alberta Parks, Alberta Health Services and the UofA’s/Augustana Campus’ Centre for Sustainable Rural Communities, this project undertook to explore the place of parks and nature in palliative care for people in rural communities. Building on 2 previous projects exploring parks inclusion for adults with disabilities and people in palliative care and their caregivers, the action research cycle included planning and visiting park sites for 1-3 hour visits for patients and families, sitting in green spaces, moving (assisted or unassisted, with a walker, or wheelchair) to a view spot of their choosing. Included in the project were 5 palliative patients and their family caregivers (including 4 spouses and 1 daughter), along with 2 rural home palliative care nurses and 1 rural hospice chaplain. Participant observations and opinions of the experience were explored. Together we discovered that experiencing “Peace in the Parks” was an opportunity for personal exploration, social discovery and park/institutional awareness.

Despite the challenges to get to parks and natural places, it was always “worth it” (and perhaps even more valuable for caregivers and family!). Everyone can make the connection with nature. Ultimately there is value in even parking or sitting in areas with views of nature or short 100 metre ‘walks’ or strolls with a stretcher or adaptive equipment. Access does takes planning, information and communication. Fundamentally, we discovered that supporting access to parks and nature for those in palliative care and their caregivers is not a call for a new program per se, but rather an invitation to the pilgrimage and sanctuary of natural places. It doesn’t always come easily or naturally but pilgrimages can be supported by a mindset influenced by training, information, and coordination. Further collaborative work is underway now to extend and expand the discoveries made thus far – the pilgrimage continues!

We most wanted to let the narrative from this project speak in the voices of our gracious park volunteers, the palliative patients, family, and professional caregivers – alongside the sounds and sites of Alberta Parks and other natural settings. The overarching narrative discovered, and the title of the short documentary film we will screen (approx. 10 min) and discuss is “Peace in the Parks”. The film can be viewed at: https://youtu.be/dkLSrzhwNzk

Rest in Peace [in the Parks] to the wonderful Bev, Ron, Liam, Garry and Maxine (with thanks to their family and caregivers).

dr. Susan Cadell, Melissa Reid Lambert, Jin Sol Kim, dr. Mary Ellen Macdonald

Background: A memorial tattoo is a tattoo that is worn by the living to honour a person who has died. Little research has been done to understand what memorial tattoos mean for grief and bereavement. The objective of this research project was to understand if and how memorial tattoos are an embodied expression of grief, and how the memorialization of the deceased impacts the bereaved person’s relationship with them.

Methods: This study was designed with qualitative description, grounded in a symbolic interactionist framework. Data collection included semi-structured interviews with bereaved tattooed adults and tattoo artists, both recruited through social media and snowball sampling. Data also included photographs of the tattoos. Analysis followed the tenets of thematic analysis.

Results: Forty-five adults were interviewed (40 bereaved participants; 5 tattoo artists). This presentation looks specifically at one emergent theme: How memorial tattoos can transform the grieving body into a site for personal and social advocacy. Tattoos were designed deliberately and placed purposefully on bodily locations, signaling public and private advocacy. Sub-themes included: wearing tattoos to resist stigmatized dying (e.g., suicide, mental health issues, overdose); using tattoos to resist stigmatized grieving (e.g., child death); and integrating tattoos as embodied vehicles for self-help and self-care.

Conclusion: Memorial tattoos are images that ink continuing bonds to the deceased. In so doing, they can also serve as embodied locations of resistance against the social stigmas that accompany death, dying and grief. This research thus expands the continuing bonds theory with important implications for bereavement research and clinical practice.

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Methods: This study was designed with qualitative description, grounded in a symbolic interactionist framework. Data collection included semi-structured interviews with bereaved tattooed adults and tattoo artists, both recruited through social media and snowball sampling. Data also included photographs of the tattoos. Analysis followed the tenets of thematic analysis.

Results: Forty-five adults were interviewed (40 bereaved participants; 5 tattoo artists). This presentation looks specifically at one emergent theme: How memorial tattoos can transform the grieving body into a site for personal and social advocacy. Tattoos were designed deliberately and placed purposefully on bodily locations, signaling public and private advocacy. Sub-themes included: wearing tattoos to resist stigmatized dying (e.g., suicide, mental health issues, overdose); using tattoos to resist stigmatized grieving (e.g., child death); and integrating tattoos as embodied vehicles for self-help and self-care.

Conclusion: Memorial tattoos are images that ink continuing bonds to the deceased. In so doing, they can also serve as embodied locations of resistance against the social stigmas that accompany death, dying and grief. This research thus expands the continuing bonds theory with important implications for bereavement research and clinical practice.

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Shaina Garfield

Shaina Garfield has bridged her design and meditation backgrounds to hold space for people grieving, as she has personally experienced how healing both can be. Founder of Leaves With You, she creates coffins and rituals for the End of Life and grief. Her most recent project, The Art of Grief Ritual, explores how using creativity with daily rituals can help one process and be present with their own grief. One way Leaves With You explores these creative rituals is through natural dyes and macrame, the process of tying and weaving rope. For Dying.dialogues, Shaina wishes to share the weaving rituals, she has created at Leaves With You, to help others through any grief a human may experience, such as grieving the death of a loved one, the collective grief of 2020, or grief over the loss of a relationship. Shaina understands that just as the right tools are needed to create a well designed product, humans need supportive tools to help them process some of the most difficult times of their life, like death and grief. She hopes that the rituals she holds space for others to create can be one tool that people have to use whenever and however grief shows up.

Katie Gach

Social technologies today are designed to presume positive experiences; “design for delight” is even a principle in user interface development (Ruberto). So when humans have inevitable negative life experiences, especially the loss of a loved one, they often take on technology-related tasks with tools that lack the capacity for compassionate and meaningful interactions. In such cases, the designs of people’s technologies can exacerbate the difficulty of their bereavement (Meyer and Wachter-Boettcher). I argue that design and engineering can and must honor the reality of human mortality by designing for postmortem data management.

Incorporating empirical work in human-computer interaction with roots in cultural anthropology, I examine the role of ritual in technologically mediated human interactions during times of grief.

Through extensive qualitative research in partnership with Facebook’s Memorialization team, I found that the experience of having a loved one’s social media profile deleted after their death contains great opportunities for consideration and improvement. Two paths of inquiry into how that improvement led me to examining rituals as the solution. The first is affective: one school of thought in affect theory states that people’s experiences of intense emotions shape their reality. Psychologist Paul Stenner employs this lens in his concept of the “liminal affective technology”: any mechanism that works to produce the desired experience in an emotional situation.

The second path of inquiry is functional: my research of the postmortem profile deletion experience identified the abruptness and totality of the deletion experience is what made it difficult for surviving loved ones. Those pain points beg the question of how to slow down and iterate the deletion process. As an anthropologist, I see rituals as a clear possible solution, as rituals can act as a liminal affective technology in forcing a slow and contemplative experience.

My current project involves interviews with survivors to understand what options for postmortem profile management may be best fitting to their needs and to the deceased’s wishes. As a trained death doula, I am able to lead my participants through their grief-related emotions to a practical set of actions and decisions. I then lead the person through the ritual as participant observer and tech support specialist. People who have completed this process with me so far have reported a heartening and healing experience. I am still seeking more people who are willing to participate in this research, but I am beginning to consider its technological applications.

Ultimately, postmortem data management is about honoring the experiences people have of the presence of the deceased within that data. If ritual-based practices around postmortem data can achieve that honor, this work will become a question of scale: how might ritual practices be implemented into systems by design?

Eric Meyer and Sara Wachter-Boettcher. 2016.Design for Real Life. A Book Apart. 132 pages. https://abookapart.com/products/design-for-real-life

John Ruberto. 2011. Design For Delight applied to Software Process Improvement.Pacific Northwest(2011).

Paul Stenner’s Liminality and Experience: A Transdisciplinary Approach to the Psychosocial (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 297 pages.

Incorporating empirical work in human-computer interaction with roots in cultural anthropology, I examine the role of ritual in technologically mediated human interactions during times of grief.

Through extensive qualitative research in partnership with Facebook’s Memorialization team, I found that the experience of having a loved one’s social media profile deleted after their death contains great opportunities for consideration and improvement. Two paths of inquiry into how that improvement led me to examining rituals as the solution. The first is affective: one school of thought in affect theory states that people’s experiences of intense emotions shape their reality. Psychologist Paul Stenner employs this lens in his concept of the “liminal affective technology”: any mechanism that works to produce the desired experience in an emotional situation.

The second path of inquiry is functional: my research of the postmortem profile deletion experience identified the abruptness and totality of the deletion experience is what made it difficult for surviving loved ones. Those pain points beg the question of how to slow down and iterate the deletion process. As an anthropologist, I see rituals as a clear possible solution, as rituals can act as a liminal affective technology in forcing a slow and contemplative experience.

My current project involves interviews with survivors to understand what options for postmortem profile management may be best fitting to their needs and to the deceased’s wishes. As a trained death doula, I am able to lead my participants through their grief-related emotions to a practical set of actions and decisions. I then lead the person through the ritual as participant observer and tech support specialist. People who have completed this process with me so far have reported a heartening and healing experience. I am still seeking more people who are willing to participate in this research, but I am beginning to consider its technological applications.

Ultimately, postmortem data management is about honoring the experiences people have of the presence of the deceased within that data. If ritual-based practices around postmortem data can achieve that honor, this work will become a question of scale: how might ritual practices be implemented into systems by design?

Eric Meyer and Sara Wachter-Boettcher. 2016.Design for Real Life. A Book Apart. 132 pages. https://abookapart.com/products/design-for-real-life

John Ruberto. 2011. Design For Delight applied to Software Process Improvement.Pacific Northwest(2011).

Paul Stenner’s Liminality and Experience: A Transdisciplinary Approach to the Psychosocial (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 297 pages.

Stephanie Saunders, Kate Hale Wilkes, Karen Oikonen, dr. Sarina R. Isenberg

In the last 20 years there has been an increase in health research reporting, largely through publishing and academic conference presentations. Although there are benefits to promoting research in this way, there is a widening gap between those who have access to this information and those who do not. Moreover, health information is often complex and may cover sensitive topics, bringing challenges to mobilizing research to the public in a meaningful way.

As a result, it has become imperative to find strategic and creative ways to engage the public. We undertook a research-through-design knowledge translation approach to disseminate our qualitative research about transitioning home at end of life (EOL) to a broader public and generate reciprocal insights. Undertaking a co-creation process, our research, clinical, and patient team partnered with an innovation design team to develop a design installation. The aim was to convey a sense of medicalization of home at the EOL through sharing research participants' experiences and incorporating symbols and images of home and home care. This installation was featured at the Toronto-based DesignTO festival in January 2020. The installation also had a participatory element whereby attendees were invited to share wishes and/or worries about transitioning from hospital to home at EOL.

Fifteen hundred visitors attended the exhibition where our installation was featured, and 100 attendees interacted with our installation. This talk will explore how we gathered input from attendees using the design installation and the synthesis process we undertook as our two disciplines' approaches content collided. Further, we discuss the findings from the installation's interaction component, with key outcomes including; concerns about being overwhelmed, hopes for a comfortable EOL experience, and regrets regarding past experiences. Last, we examine the implications of these findings on future research.

We interpreted this entire process as a research-to-public feedback loop, whereby attendees both had the opportunity to learn about EOL research and contribute to it with tangible results that can support future research. Overall, making use of research-through-design resulted in a research-to-public feedback approach that can be trialed in various contexts outside EOL.

As a result, it has become imperative to find strategic and creative ways to engage the public. We undertook a research-through-design knowledge translation approach to disseminate our qualitative research about transitioning home at end of life (EOL) to a broader public and generate reciprocal insights. Undertaking a co-creation process, our research, clinical, and patient team partnered with an innovation design team to develop a design installation. The aim was to convey a sense of medicalization of home at the EOL through sharing research participants' experiences and incorporating symbols and images of home and home care. This installation was featured at the Toronto-based DesignTO festival in January 2020. The installation also had a participatory element whereby attendees were invited to share wishes and/or worries about transitioning from hospital to home at EOL.

Fifteen hundred visitors attended the exhibition where our installation was featured, and 100 attendees interacted with our installation. This talk will explore how we gathered input from attendees using the design installation and the synthesis process we undertook as our two disciplines' approaches content collided. Further, we discuss the findings from the installation's interaction component, with key outcomes including; concerns about being overwhelmed, hopes for a comfortable EOL experience, and regrets regarding past experiences. Last, we examine the implications of these findings on future research.

We interpreted this entire process as a research-to-public feedback loop, whereby attendees both had the opportunity to learn about EOL research and contribute to it with tangible results that can support future research. Overall, making use of research-through-design resulted in a research-to-public feedback approach that can be trialed in various contexts outside EOL.

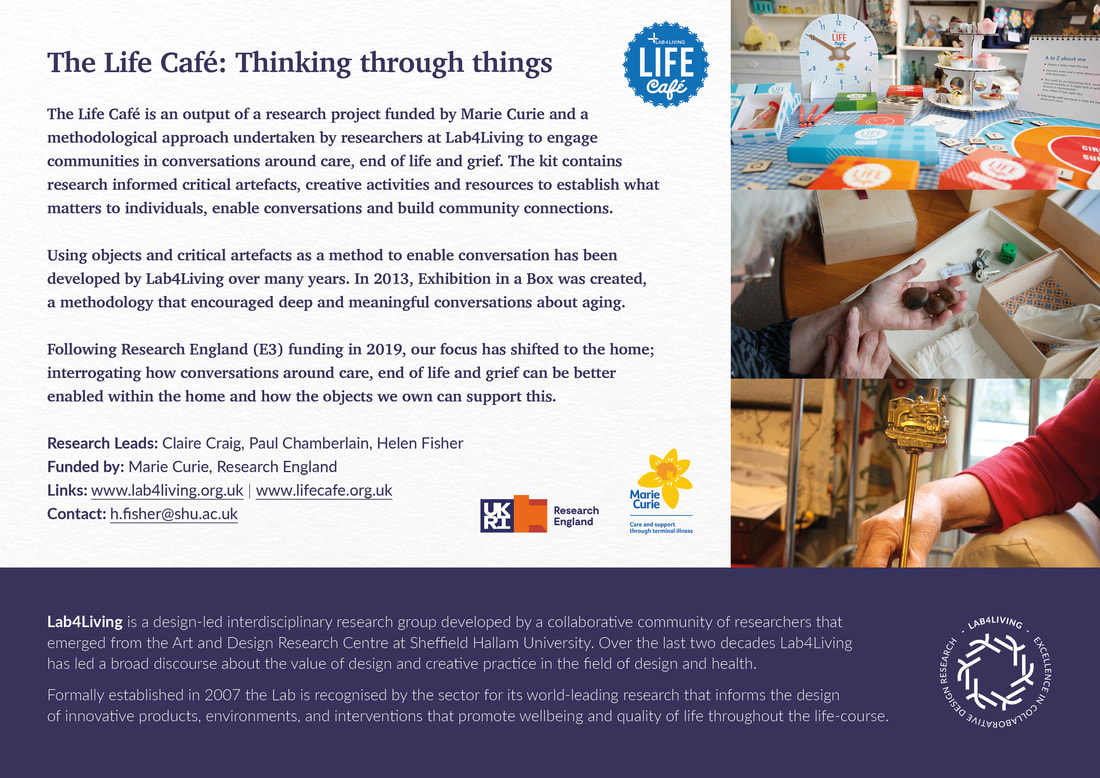

Lab4living (Helen Fisher, dr. Claire Craig, dr. Paul Chamberlain)

The last decade has witnessed a demographic change on unprecedented scale - people are living longer and with more complex, long term conditions and yet the topic of dying still remains taboo. This short talk / poster shares the Life Cafe, an output of a research project funded by Marie Curie and a methodological approach undertaken by researchers at Lab4Living, Sheffield Hallam University, to engage communities in conversations around care, end of life and grief and how Covid-19 has shifted our thinking.

The Life Cafe, initially designed as a research methodology, is now on the market as a kit of research informed critical artefacts, creative activities and resources to establish what matters to individuals, enable conversations and build community connections.

The method of using objects as critical artefacts to enable conversation has been developed by Lab4Living over many years. In 2006, the director of Lab4Living published a paper about the ‘‘Designers’ Use of the Artefact in Human centred Design’ which highlighted ‘how artefacts can be used as an effective tool to understand users and encourage dialogue’ (Chamberlain, 2006).

In 2013, Lab4Living developed Exhibition in a Box. ‘The principles of the traditional exhibition were distilled into a format that was more flexible, accessible and inclusive. ‘Exhibition in a box’ (Chaimberlain & Craig, 2013) took the essence of the exhibition into a suitcase, á la Duchamp that could be transported to diverse environs including the home. The boxes comprised of everyday objects, photographs and textual material defined through the user-workshops.’ (Lab4Living.org.uk, n.d.)

Building on these methods, through an iterative co-design process, the Life Cafe resulted in incorporating 9 objects in the kit. These objects represent the 9 themes of conversation following a thematic analysis of Life Cafes undertaken with 141 members of the public.

The Life Cafe not only traditionally generates meaningful thought around care, end of life and grief through objects, it creates a safe, comfortable space for conversation through the design of the materials that set the scene, the use of photographs and other creative and interactive activities.

The Life Cafe was developed between 2017 - 2019 in response to the ageing population and our need to better communicate about what matters to individuals and communities in relation to care, end of life, death and grief. In some respects, the Covid-19 pandemic has been a wake up call demonstrating that these conversations need to happen now but has also halted group interventions such as the Life Cafe which offered a physical, tangible experience; a space and place to engage in meaningful conversations.

This short talk / poster explores the role that design has to play in translating the essence of interventions like the Life Cafe into something that can be as meaningful but facilitated remotely and how methods such as object elicitation can be effectively enacted in the ‘new normal’.

Taking inspiration from other interventions developed by Lab4Living, such as Journeying Through Dementia - Delivered, we recognize that digital isn’t always the answer, posing interesting questions about how we engage people in a human way when face-to-face interaction isn’t an option. Although initiated by Covid-19, this body of design research has the ability to be applicable to many projects going forward with the hope of generating more accessible solutions and ways for people to engage in research or interventions such as the Life Cafe remotely.

The Life Cafe, initially designed as a research methodology, is now on the market as a kit of research informed critical artefacts, creative activities and resources to establish what matters to individuals, enable conversations and build community connections.

The method of using objects as critical artefacts to enable conversation has been developed by Lab4Living over many years. In 2006, the director of Lab4Living published a paper about the ‘‘Designers’ Use of the Artefact in Human centred Design’ which highlighted ‘how artefacts can be used as an effective tool to understand users and encourage dialogue’ (Chamberlain, 2006).

In 2013, Lab4Living developed Exhibition in a Box. ‘The principles of the traditional exhibition were distilled into a format that was more flexible, accessible and inclusive. ‘Exhibition in a box’ (Chaimberlain & Craig, 2013) took the essence of the exhibition into a suitcase, á la Duchamp that could be transported to diverse environs including the home. The boxes comprised of everyday objects, photographs and textual material defined through the user-workshops.’ (Lab4Living.org.uk, n.d.)

Building on these methods, through an iterative co-design process, the Life Cafe resulted in incorporating 9 objects in the kit. These objects represent the 9 themes of conversation following a thematic analysis of Life Cafes undertaken with 141 members of the public.

The Life Cafe not only traditionally generates meaningful thought around care, end of life and grief through objects, it creates a safe, comfortable space for conversation through the design of the materials that set the scene, the use of photographs and other creative and interactive activities.

The Life Cafe was developed between 2017 - 2019 in response to the ageing population and our need to better communicate about what matters to individuals and communities in relation to care, end of life, death and grief. In some respects, the Covid-19 pandemic has been a wake up call demonstrating that these conversations need to happen now but has also halted group interventions such as the Life Cafe which offered a physical, tangible experience; a space and place to engage in meaningful conversations.

This short talk / poster explores the role that design has to play in translating the essence of interventions like the Life Cafe into something that can be as meaningful but facilitated remotely and how methods such as object elicitation can be effectively enacted in the ‘new normal’.

Taking inspiration from other interventions developed by Lab4Living, such as Journeying Through Dementia - Delivered, we recognize that digital isn’t always the answer, posing interesting questions about how we engage people in a human way when face-to-face interaction isn’t an option. Although initiated by Covid-19, this body of design research has the ability to be applicable to many projects going forward with the hope of generating more accessible solutions and ways for people to engage in research or interventions such as the Life Cafe remotely.

Chiara Di Michele

The project analyzes the socio-semiotic and anthropological conditions of mourning. It investigates the reasons that drive society to adopt certain behaviours and the symbolic mediations that allow the transmission of memory. Persephone is a project that takes on both a scientific and a humanistic approach, it studies and connects many disciplines and experiments different ways to analyze the relationship between humans and death. The work aims to raise questions and new ideas for a positive approach in a contemporary western world that tends to elude death.

The object is to innovate meanings & technologies, proposing a new interpretation through a product. Design could apply its potential to other subjects than products as traditionally understood, indeed the paper wants to make the potential user to reflect on the profound theme of death.

Isn’t design supposed to lead the society towards meaning and technology innovation? So why does it keep out the death of his concerns and action? In today's society death is an enemy to fight, instead of being the unavoidable end of life. The understanding of death is defined by myths and social rituals and it’s charged with ethics, juridical, scientific and religious implications. Therefore is considered by the contemporary consumerist society not only as a taboo, but also as a contradiction. So we tend to push it away in order to neutralize it.

Persephone adopts demographic, ethnographic and anthropological on desk research, to understand how the people's perception of death has changed throughout the times (from ancients to digital death). In addition, insights here analysed were made through fieldwork, that includes a series of dialogue sessions and discussions on a sample of more than one hundred people from different cultures and ages.

Every culture is different, everyone has its own traditions, but in any way we everybody makes rituals.

Since ever we live death only in the other ones. Persephone lamp takes this opportunity to symbolically recreate a communication experience through the element of light, and it does so in today's cultural context, where the centre of change are humans relying on objects.

Objects spread meanings, convey emotions, and this is what Persephone is conceived to work on. Light, life generating principle, meets its opposite and complementary: death, the end of the being.

This symbolic action allows us to identify the interaction with the light as an incentive to remember in these fast times.

We establish a dialogue with our memories of a dead person, through an activation gesture and a light time duration.

We customize everything and produce a serious overabundance of objects in any field and for any needs but when we face the implications that death brings to society, everything ceases.

Are we, as designers, projected toward new forms of design?

The object is to innovate meanings & technologies, proposing a new interpretation through a product. Design could apply its potential to other subjects than products as traditionally understood, indeed the paper wants to make the potential user to reflect on the profound theme of death.

Isn’t design supposed to lead the society towards meaning and technology innovation? So why does it keep out the death of his concerns and action? In today's society death is an enemy to fight, instead of being the unavoidable end of life. The understanding of death is defined by myths and social rituals and it’s charged with ethics, juridical, scientific and religious implications. Therefore is considered by the contemporary consumerist society not only as a taboo, but also as a contradiction. So we tend to push it away in order to neutralize it.

Persephone adopts demographic, ethnographic and anthropological on desk research, to understand how the people's perception of death has changed throughout the times (from ancients to digital death). In addition, insights here analysed were made through fieldwork, that includes a series of dialogue sessions and discussions on a sample of more than one hundred people from different cultures and ages.

Every culture is different, everyone has its own traditions, but in any way we everybody makes rituals.

Since ever we live death only in the other ones. Persephone lamp takes this opportunity to symbolically recreate a communication experience through the element of light, and it does so in today's cultural context, where the centre of change are humans relying on objects.

Objects spread meanings, convey emotions, and this is what Persephone is conceived to work on. Light, life generating principle, meets its opposite and complementary: death, the end of the being.

This symbolic action allows us to identify the interaction with the light as an incentive to remember in these fast times.

We establish a dialogue with our memories of a dead person, through an activation gesture and a light time duration.

We customize everything and produce a serious overabundance of objects in any field and for any needs but when we face the implications that death brings to society, everything ceases.

Are we, as designers, projected toward new forms of design?

Amberlie Perkin

I will share how after experiencing 3 personal losses in the first year of my degree my practice and research pivoted from environmental concerns to the exploration of death, grieving, and the fragility of the body. I will share how grief informed my methodology for making, and how I came to create sculptural installations as public communal spaces for contemplating fragility and loss while acknowledging both individual and collective grief.

My thesis entitled Honouring Ghosts & The Nature of Grief is a project rooted in relationships─ the deep bonds which we share with one another, with our more-than-human kin, and our relationship with the abundant animate life that exists in the natural world. After losing several loved ones to cancer in a short time I became drawn to the interplay of grief and wounded ecology. I began to perceive the body as a wounded ecology when fraught with illness, and our relationships as wounded ecologies when we experience the death of our kin. This new way of thinking led to a methodological framework for making which involves thinking with grief and thinking with and through nature.

Through curious and embodied engagement with the natural world, I developed a material vernacular for grief using the formal and metaphoric language of nature. The questions I address through my creative research are:

How is the transformational nature of grief enacted through the intuitive, embodied, material, and metaphoric processes of making?

How can the absence created by death be materially and conceptually made present through space and form?

The research takes a phenomenological approach through walking, observing, sensing, and collecting organic ephemera in the natural environment. My embodied experiences in the natural world and the organic matter I’ve collected (lichen, shed bark, and fragmented tree stumps) are then translated through various material investigations in the studio including relief printing, repetitive layering to build up forms, generating 3D sculptures, and finally, creating largescale immersive installations.

Tracing Your Ghost II is a participatory installation which borrows language and processes from nature ─tracing the lines of time, layering, cocooning, and shedding; all the while enacting new cycles of transformation through the process of making. This grouping of suspended delicate paper sculptures invites the viewers walking amongst them to contemplate absence, fragility, and the resonance of the human body found in the intricate organic forms.

In my talk I will share the ways in which my creative research and artworks elucidate the complex and often abstract experiences of grief, while giving material form to absence and loss. I will assert the generative potential in art installations to create spaces for people to feel, to remember, to acknowledge their grief in public, and to commune with ghosts.

My thesis entitled Honouring Ghosts & The Nature of Grief is a project rooted in relationships─ the deep bonds which we share with one another, with our more-than-human kin, and our relationship with the abundant animate life that exists in the natural world. After losing several loved ones to cancer in a short time I became drawn to the interplay of grief and wounded ecology. I began to perceive the body as a wounded ecology when fraught with illness, and our relationships as wounded ecologies when we experience the death of our kin. This new way of thinking led to a methodological framework for making which involves thinking with grief and thinking with and through nature.

Through curious and embodied engagement with the natural world, I developed a material vernacular for grief using the formal and metaphoric language of nature. The questions I address through my creative research are:

How is the transformational nature of grief enacted through the intuitive, embodied, material, and metaphoric processes of making?

How can the absence created by death be materially and conceptually made present through space and form?

The research takes a phenomenological approach through walking, observing, sensing, and collecting organic ephemera in the natural environment. My embodied experiences in the natural world and the organic matter I’ve collected (lichen, shed bark, and fragmented tree stumps) are then translated through various material investigations in the studio including relief printing, repetitive layering to build up forms, generating 3D sculptures, and finally, creating largescale immersive installations.

Tracing Your Ghost II is a participatory installation which borrows language and processes from nature ─tracing the lines of time, layering, cocooning, and shedding; all the while enacting new cycles of transformation through the process of making. This grouping of suspended delicate paper sculptures invites the viewers walking amongst them to contemplate absence, fragility, and the resonance of the human body found in the intricate organic forms.

In my talk I will share the ways in which my creative research and artworks elucidate the complex and often abstract experiences of grief, while giving material form to absence and loss. I will assert the generative potential in art installations to create spaces for people to feel, to remember, to acknowledge their grief in public, and to commune with ghosts.

Anne Isabelle Leonard

In July and August 2020 at Galerie AVE, kneeling over a large roll of paper, charcoal in hand, Anne Isabelle traced the portraits of beloveds who have passed away. With her eyes closed, the artist revisited the lines of her memories, the drawings a pretext to spend a moment with the deceased. The incomplete nature of the sketch as well as the inaccuracy of the exercise expresses the fading reconstruction of what is left of these memories -- allowing the performer a moment of grief. In this new digital version of the performance, Anne Isabelle invites her audience to experience this exercise in their own time and personal space (or outside on the asphalt) by following the instructions posted on this page. By bringing this performance to the public digital sphere through a performative and participatory approach, the artist wishes to offer a space for conversation, sharing, and acceptance of vulnerability bonded to loss. People will be able to share and post their drawings if they wish and to join Anne Isabelle in a live guided performance of the piece on January 30 at 1:50pm.

Poster - Lab4Living

Peace in the Parks

Supported by Mount Royal University (MRU), Alberta Parks, Alberta Health Services and the UofA’s/Augustana Campus’ Centre for Sustainable Rural Communities, this project undertook to explore the place of parks and nature in palliative care for people in rural communities. Building on 2 previous projects exploring parks inclusion for adults with disabilities and people in palliative care and their caregivers, the action research cycle included planning and visiting park sites for 1-3 hour visits for patients and families, sitting in green spaces, moving (assisted or unassisted, with a walker, or wheelchair) to a view spot of their choosing. Included in the project were 5 palliative patients and their family caregivers (including 4 spouses and 1 daughter), along with 2 rural home palliative care nurses and 1 rural hospice chaplain. Participant observations and opinions of the experience were explored. Together we discovered that experiencing “Peace in the Parks” was an opportunity for personal exploration, social discovery and park/institutional awareness.

For more information contact Jennell Rempel at [email protected] and/or Dr. Sonya Jakubec at [email protected]

For more information contact Jennell Rempel at [email protected] and/or Dr. Sonya Jakubec at [email protected]

Artist Panel Artwork

Cailleah Scott-Grimes

Rockin the Coffin' (2020)